Dying for Wine? South African Farm Workers Battle Toxic Pesticide Trade with EU

When Dina Ndelini had spent over four decades tending to vineyards near Cape Town, she abruptly experienced severe shortness of breath. Her visit to the medical facility soon led to a cascade of unfortunate occurrences resulting in the loss of her well-being, employment, and consequently, her residence.

As per her physician, the primary suspect appeared to be exposure to a chemical mixture called Dormex. This substance is frequently employed as a plant growth regulator in South Africa; however, its main component, cyanamide, has been noted for its significant danger. EU Chemicals Agency (ECHA) and prohibited in the European Union since 2009.

Nevertheless, Dormex is merely one of many. long list Of highly dangerous chemicals that continue to be manufactured within European territories and exported to other nations. Subsequently, food products created overseas utilizing these chemicals are imported and placed on sale in Europe’s supermarkets.

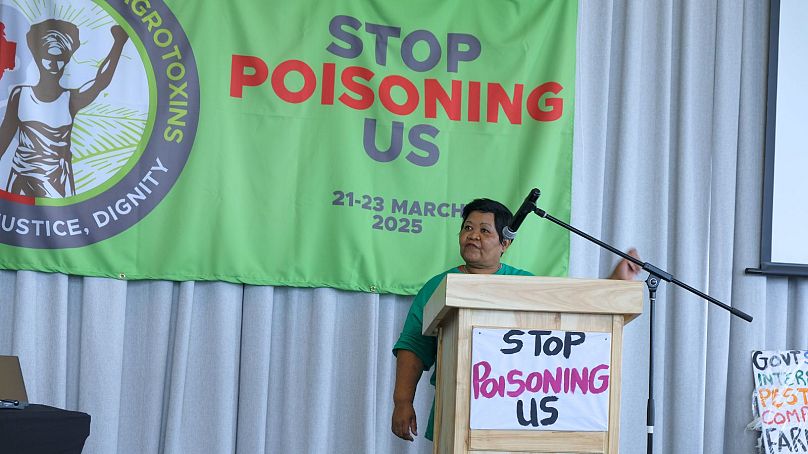

One of the numerous accounts recounted by farmworkers along with legal and healthcare experts was Dina’s, which emerged during a recent gathering. People’s Tribunal on Agrotoxins , which occurred from 21-23 March in the midst of the renowned Stellenbosch wine country.

Although not an official courtroom setting, these community-organized tribunals offer a platform where individuals affected can recount their experiences before knowledgeable adjudicators who assess claims related to breaches of international laws, covering areas such as environmental issues and human rights abuses.

South African farmworkers appeal to Europe to cease shipping 'poisons'

When asked for her message to Europe, Dina was straightforward. "As agricultural laborers, we've had enough—we do not want more of these pesticides coming from Europe," she states, encouraging the European Union to "cease sending us harmful substances."

Throughout the two-day tribunal, this sentiment was repeated numerous times as agricultural laborers testified about how pesticide exposure had affected them, describing issues such as respiratory problems, ovarian cancer, and diminished eyesight.

If it doesn’t meet their standards in Europe, then why would they think it’s acceptable here?" asks an unnamed agricultural employee, emphasizing that European buyers ought to be aware of "the true human conditions underlying these products. wine they are drinking”.

As stated by the African Centre for Biodiversity, 192 highly hazardous pesticides are still officially used in South Africa , with 57 being prohibited for use within the European Union. Several of these are known to be neurotoxins or carcinogens, whereas others are classified as highly harmful to the environment.

The individuals most exposed are the farm workers and their families residing near pesticide application areas. They find themselves at the bottom of the nation’s intricate socio-economic hierarchy, which stems from its history of apartheid.

Frequently overburdened, undercompensated, and inadequately safeguarded due to tenuous employment agreements, farm laborers wield minimal influence regarding the management of these properties, overseen by affluent landowning farmers known as 'boers'.

Those most at risk include women, who are disproportionately affected. more biologically prone to pesticide exposure and more vulnerable In South African communities, as stated by South Africa’s Women on Farms project (WFP), an organization focused on safeguarding female agricultural employees in the Western and Northern Cape.

During the hearing, workers consistently stated that they were not supplied with personal protective gear. Many testified that female employees often use scarves to shield their faces during their shifts. Some also mentioned lacking access to running water or toilet facilities within the vineyard areas.

Prohibited pesticide exports described as 'a clear case of double standards'

Efforts to harmonize trading practices are under the microscope in Brussels, following the release of a fresh EU agricultural policy blueprint that outlines strategies to limit food imports from non-EU nations containing pesticide residuals prohibited within Europe.

This isn’t the first instance where the EU has contemplated taking similar actions; whispers about the Commission potentially halting the export of prohibited pesticides have been around for years.

However, the proposals encounter strong resistance from agricultural industry organizations, such as pesticide lobbying group CropLife, which has consistently maintained that these measures pesticides become essential under specific conditions.

“Given the distinct production circumstances within South African agriculture, comparing it with other nations and regions becomes challenging,” statedCropLife South Africa after the tribunal. They assert that varying crops, pests, and weather conditions necessitate ‘tailored approaches and pesticides applied at specific intervals’.

This point doesn’t carry much weight for UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights, Dr Marcos Orellana. He states, "The human body is identical across all regions; the discrepancy lies in the inadequate capability of governmental organizations to manage the dangers faced by individuals in precarious conditions." He labels this as a clear case of "a blatant double standard".

International safeguards reduced to a 'checklist' task

South Africa Does have legal frameworks regulating the use of these chemicals and plans to phased out highly dangerous pesticides soon, however, those involved in the tribunals contended that enforcement is frequently inadequate. In addition, agricultural laborers are typically uninformed about or hesitant to push for their entitlements.

For the UN’s Orellana, the argument that governments are sovereign to make their own decisions “underscores [the] lack of capacities in many, if not most, developing countries involved in international trade of pesticides” and excludes the issue of “corruption and corporate capture of the government institutions that make these decisions”.

More broadly, an international agreement known as the Rotterdam Convention is aimed at promoting well-informed choices for nations involved in trading hazardous chemicals.

However, according to Dr Andrea Rother, who leads the environmental health department at the University of Cape Town, the convention is overly complex and fails to achieve its intended effectiveness. She explains that "by the time a pesticide makes it onto the list, it’s usually outdated." Furthermore, she suggests that the convention functions more as a mere formality—a simple 'check-the-box' procedure—rather than serving as an authentic protective measure.

Highlighting that no African nation produces its own pesticide components, Rother believes that an embargo from the European Union would significantly assist South Africa.

“She suggests that there are alternative options to these pesticides,” asserting that an export ban could act as a “trigger” for moving toward greater adoption of them. sustainable agricultural systems .

According to Kara MacKay, who serves as the campaigns coordinator for WFP, every day that the EU persists in producing and exporting these banned pesticides within Europe to South Africa makes them "accomplices in the ongoing pesticide poisoning of agricultural workers and residents."

"We need to put an end to this harmful practice—suggesting otherwise demonstrates a racially biased and colonially minded approach that lacks justification," she states.

Meanwhile, the expert judges presiding over the People’s Tribunal will review the evidence submitted by Dina and the other farmworkers, then provide their judgment along with legal recommendations in several months.

Posting Komentar untuk "Dying for Wine? South African Farm Workers Battle Toxic Pesticide Trade with EU"

Please Leave a wise comment, Thank you